My screenplays are based on social issues: Identity, racism, trauma, loss, disability, child abuse, fostering, mental health, ageing, infertility, and bullying. Those don’t have to be heavy dramas.

Single foster parent, aid worker, chaos specialist. Phoenix, the child of immigrants, writes genre-benders about identity, racism and loss. Her social dramas, blended with whatever the muse brings, are told from her perspective as a woman of colour with a disability. Phoenix is inspired by her son, who thinks he’s a dragon, and muse, Keanu Reeves. Neither of them does the dishes.

Every writer has a unique Point Of View. I speak only from my own experience. I was not raised on movies. I have not been a screenwriter for my whole career. Still, I hope this resonates with you. – Phoenix Black

A great story often moves from an idea to fruition with a trigger. What was yours?

Sometimes it’s based on assignment or set criteria. For example, I had to write a horror short for a competition about a stagehand and a shadow. I’d never written horror. That formed the basis of my feature FATHER TRINITY (formerly BONEYARD). I’m currently outlining a potential sequel to a ’70s film. The prequel directs the sequel. I might read an article or eavesdrop on a conversation. A stranger tells me their life story in a café. I have one of those faces. My best line of dialogue came from a woman giving me a bikini wax. One of those ideas reaches out and pulls me in.

At the risk of sounding drug-addled, my writing often feels… spiritual. Not in a religious way. I’m consciously or unconsciously wrestling with a question or struggling. Someone unseen listens and responds, ‘Let me tell you a story,’ or ‘Let me show you.’ I had a vivid image of a boy, alone on a beach in Sri Lanka. I knew I had to find him. It doesn’t mean the story is good or gets finished.

I once did CPR on an old woman whose son-in-law ran off the road. This was in Cambodia, when I was working on the avian influenza pandemic response. Bodies and blood everywhere. Their toddler survived without a scratch. I couldn’t save the old woman.

I swear her spirit stuck to me for three days.

Writing is similar. My characters arrive fully formed. They live with me. They stick to me.

My writing is an abstraction of my life, in the plot, characters or themes. I’m not a saint. I’ve done a lot of stupid things. I wear my heart on my sleeve, which is not a safe place to keep it. That’s a great way to write but not a wise way to live. I’ve had an eclectic life, with an abundance of joy, intense love, adventure, hardship and trauma.

My first son, Phoenix, died late into the pregnancy. I started fostering my second son – let’s call him Andy – just before lockdown. They are my two major triggers in recent writing.

Andy hurt himself at soccer. His coach said, “No tears.” I wondered, how would a boy brought up with that mantra cope with profound loss? How do I bring up this sweet boy to not be a toxic man? Those questions and my horror short came together to form Father Trinity.

Andy and I watched How To Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World. Then, Andy decided he was a dragon. At night, he dreamed he had adventures in a dragon world, rolling his reality into his fantasy. In the day, he was a ball of rage and neediness. Keanu was our imaginary housemate. He was blamed for stray farts and chocolate wrappers under the couch. Writing was a salve. KEANU REEVES IS MY MUSE, MY SON IS A DRAGON is based on our true story.

My screenplays are based on social issues: Identity, racism, trauma, loss, disability, child abuse, fostering, mental health, ageing, infertility, and bullying. Those don’t have to be heavy dramas.

I don’t want to watch a heavy drama about a grieving orphan. Yet, I’ll watch Harry Potter.

Writing one screenplay is equal to years of therapy. Each story grants me insight into myself. You observe yourself – or part of yourself – as a character. A level of impartial distance helps you understand what happened to you. I’ll watch my character and think, ‘No, don’t do it. It’s going to end badly.’ And then she does it. I see where it all went wrong. I feel compassion for her and, thereby, for myself.

I don’t finish every project. Sometimes, you’re too close to it. Sometimes, you fall out of love with your story. Like any relationship, you must know when it’s time to end it.

How did Keanu Reeves become your muse?

I was approaching fifty-two. I had been on the foster-to-adoption list for over two years. I was still grieving the loss of my baby boy. Everyone I knew had kids or had decided against having them. No one understood my grief. No one could help me answer: ‘Is it too late to have kids?’

I came across an old Esquire article. Keanu Reeves was being interviewed. He said, “It’s too late. It’s over. I’m fifty-two. I’m not going to have any kids.” After that, dozens of things happened in a short space of time. My tiny local theatre ran a Keanu-a-thon. The Sydney Fringe Festival staged a play of Speed on a bus. The guy buying my fridge was called Neo. It went on and on and on. It was bizarre. I’d laugh about it with friends.

So – try to suspend judgment – I wrote a letter to Keanu Reeves. Not the craziest thing I’ve done. Keanu talked about grief the way I felt it: “Grief changes shape, but it never ends. People have a misconception that you can deal with it and say, ‘It’s gone, and I’m better.’ They’re wrong. When the people you love are gone, you’re alone.” That’s exactly how I felt.

That letter was a way to process my decision. I decided not to have a child.

Keanu became my muse. I started writing in a way that I’d never written before. Every time I’d get stuck, some version of him – from Johnny Utah to John Wick – got me unstuck.

I wasn’t a Keanu fan before this happened. At that time, I was in lockdown with Andy. Andy was an angry stranger. I locked my door and hid the knives. I wasn’t sleeping. Keanu kept coming up in my feed. His cult-like status amused me, his fans from adoring to zealots. Some of it’s spit-out-your-drink funny. There’s a website devoted to him being immortal!

I love the love that surrounds him. No one else inspires such unadulterated goodwill. I felt like he wrote with me. Does that make him my inspiration or an echo of my grief? Whatever it is, it works.

Two weeks after I wrote to Keanu, I got the call. A nine-year-old boy needed a home.

Since then, Keanu is in every script I write.

So you see muses as real?

Many believe in an invisible God guiding their lives. We (I hope) all believe in the laws of physics, we sightlessly see. Many creatives believe in a muse. They bear the words of a song or a poem. We hear them in the tentative tinker of a piano or the grief of a cello. We see them in the fall of fabric, the confluence of ideas or the flurry of words.

I can intellectualise it, but I cannot explain it. Nevertheless, I do believe in the muse. Fervently.

Fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy believed his gift was God-given, but his muse was Audrey Hepburn. In return, she said he was “far more than a couturier; he is a creator of personality.” There was a symbiotic creative relationship. She inspired his creations. In return, his fashion created a character for her.

Obviously, I don’t know Keanu. I write him as the male version of myself, melded with research. My dad died two weeks after my son’s funeral. The whole Keanu kismet weirdness happened on the third anniversary of their deaths. Maybe I needed a friend, even if he was imaginary.

Perhaps muses are the embodiment of our story or our purpose. It is not only the nexus of genetic gifts and nurture that makes us writers. Why does a story come to one person rather than another? Are spirits or ancestors whispering in our ears? Are muses the vestigial organ of a lifetime of experience? If you take away nature and nurture from what makes a person, you are left with the soul. That is where the essence of creativity, the muse, exists.

Have you always known that you could write?

I have a Bachelor of Applied Science (Physiotherapy/Physical Therapy). I have a Masters of Public Health. Even in my forties, my parents said, “You can always go back and study medicine.” In my culture, being a writer wasn’t a career possibility. It was doctor, lawyer, accountant or wife.

My cousin was a famous playwright in Sri Lanka. My mother always said – in a loud whisper – “She’s a lesbian.” Being a writer – like being a lesbian, according to my mother – was a radical choice.

Whether I could write was judged from an external frame of reference. I did well at English at school. Friends laughed at my emails about my aid worker sexscapades. I did a raft of short courses. I studied copywriting. I interned with Saatchi & Saatchi. Our group discussed our mentor’s brown and tan checked pony skin shoes for half an hour. After that, I knew advertising wasn’t for me.

I studied novel writing with Allen and Unwin’s Faber Academy and was published in their anthology. I studied advanced playwriting with playwright Timothy Daly. I was long-listed for a theatre writing commission. I studied screenwriting. I learned absolutely nothing. I studied filmmaking, where I co-directed a short. That led to me being a production manager on a professional short film, Final Broadcast.

When I finished Father Trinity, I got positive feedback from a mentor. I scored 8 on the Blacklist. I placed at the PAGE Awards and Austin Film Festival.

Father Trinity is a polarising script, in a Mulholland Drive kind of way. I paid for a lot of professional feedback. That process refined my craft. I finally knew that I could write. Not in the way other people write. My writing is rooted in a different cultural framework. I have epilepsy, so my neurons spark in a different way.

One mentor said, “People will hate it or think you’re a mad genius, but no one will say Meh!”

The most significant creative milestone is to know that your work is good, without requiring the validation of others.

Is your personal story commonplace with other screenwriters? Why?

No. I’ve been discouraged from telling my personal story. “There’s too much going on.” “Managers won’t know how to sell you.” A backstory can’t be one “that’s a lot.” Tragedy still has to be upbeat.

Writers are a product. We have to have a neat logline. We must compress a lifetime of experience into a paragraph.

My parents landed in Australia during the White Australia Policy in 1963. Mum sat perched on her suitcase in front of the large tin shed that was the airport. A leathery-faced woman asked,

“Did ya come ‘ere to die?”

Mum sipped her tea as she told the story for the hundredth time. I saw her with her beehive hairdo, large sunglasses, and her tight capris pants. She looked impossibly glamorous.

“And I thought, what have we got ourselves into? This is a savage place!”

It was nothing but red dust and far from the civility of London, where she met Dad, or Sri Lanka, where they spoke the Queen’s English.

“Or did ya come here yesta-die?”

I always laughed, not just because it was funny. Mum was the girl who stole food to eat from her neighbour’s garden. Life had been savage, something to survive, and she was here now in The Lucky Country.

Dad was one of the first dozen people of colour allowed into Australia. He was admitted under a professional program. He set up the anatomy department in one of the country’s largest medical schools. My parents were Sri Lankan hipsters. Mum was white, with a Dutch and English heritage. Dad ticked Black on the immigration tick box. Kids chased me up trees shouting, “Blackie!” In 1970s Australia, ‘Black’ meant Aboriginal, or anyone like me.

I was the first person of colour most people had seen. I spent my first class (around age 6) in England, in Sussex and Newcastle. In one, I was an exotic celebrity, like a kangaroo in the playground. In the other, no teacher or child acknowledged or spoke to me. Not one word for six months. When we returned to Australia, I couldn’t read.

I was a very sick child, in and out of doctor’s offices and hospitals. That profoundly impacts a family’s dynamic. My sister was volatile. We walked on eggshells. There was a lot of door slamming.

My parents were torn between keeping me well and keeping my sister happy. They worked sixteen-hour days. My sister was beautiful, charming, and funny. I remember her crying because she had to choose between three men who were in love with her. She shouted, “You don’t know what it’s like to be a passionate person!” I grew up in a comedic war zone.

From age four to eighteen, I waited tables at Mum’s restaurant. I visited Dad at the university after school. He taught medical students and dissected dead bodies. I’d open Dad’s fridge. A chilli and sambol sandwich was nestled next to a half-dissected hand. Dad would maître d’ at the restaurant until midnight. I pretended to be asleep as he carried us to bed, up seventeen steps.

The restaurant was a colourful place for a child. Full of big personalities, romance, stoned waiters and drunk customers. The waiters were arty intellectuals, five years older than me. They felt the need to educate me. We recited poetry at picnics. We talked about books and plays. It was all very Brideshead Revisited, but without the river punting.

I grew up with openly gay men, which was unusual in the 1970s. Sexuality was interesting, like the colour of someone’s eyes, but not something to judge.

When I was sixteen, I dated a twenty-one-year-old waiter in our restaurant. What were my parents thinking? What was he thinking? He ignited my interest in movies: Amadeus, Kiss of the Spider Woman, Blue Velvet, The Fly, Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down, Wild At Heart, Like Water For Chocolate, and Amélie. They all had a sensual grandeur.

High school was dominated by my epilepsy. That’s another story.

My parent’s expectation was that I’d be a doctor. If I got ninety-five percent on a test, Mum would ask, “What happened to the other five?” I didn’t feel pressure from my parents. Instead, I thought, ‘What did happen to the other five percent?’ A mark of ‘B’ is an Asian ‘F.’ It’s a stereotype, but not one based on nothing.

After flunking my med school interview, I studied dentistry and physiotherapy (physical therapy). I lasted less than three years as a physiotherapist. My skills lay in leadership. I managed a disability education department. I managed operations teams at the Sydney Olympics. Then, I moved into pharmaceutical education and research. It didn’t sit well.

I eventually found my calling. Despite my parent’s protests, I moved to Cambodia at age thirty-nine as an aid worker. I worked in avian influenza and pandemics with the World Health Organisation.

I worked in Myanmar after Cyclone Nargis, under the close watch of the military junta. I convinced the province’s medical director to train doctors in abortion and assisting rape survivors. I travelled by speedboat, helicopter, or motorcycle, to my work in remote villages.

In Sudan, I worked in water, sanitation and hygiene. I led an outbreak investigation in rebel-controlled areas. The Rwandan military escorted us in a long army convoy through the desert, with an ambulance in case we got shot. Angry rebels and child soldiers swarmed our medical truck.

Haiti was next. After the earthquake, I was part of Oxfam America’s response team. A cyclone, election violence, and cholera soon followed. I moved to The International Organization for Migration, inside the UN compound. I went to the base café. Sean Penn and Patricia Arquette were eating at the next table. Eighteen months later, I was just minimising the damage caused by politics and other ex-pats.

I complained to a colleague about how dysfunctional our colleagues were. She answered, “We are all dysfunctional.” I thought, ‘We are all damaged.’ How could we not be? My feet didn’t touch the ground in eighteen months without a man guarding me. One of my friends was kidnapped and tortured in Syria for fourteen months. Devastation becomes normal. It’s much like an ambulance worker or nurse in a sexual assault clinic, I guess. If you felt it all, you couldn’t do your job.

In Haiti, I often saw a naked man walking on the street as I was driven to work. He was always beaming, happy in his own mad world. It was better than being in an asylum. Then, one day, he was wearing a clean white business shirt. I cried for the first time. I cried because I’d felt nothing. It had never occurred to me to give him clothes. Was I a compassionless monster?

When I came back, nearly five years later, Dad had something like Motor Neuron Disease. His speciality was neurology. It was ironic that no one could diagnose his rare condition.

I worked in government: Health policy, and then the Fire Service. ‘Firies’ were predominantly white men. They were called ‘Yellow Angels’ after their yellow uniforms. By then, I was a bit of an expert in rapid behaviour change and cognitive bias. I was hired to redirect the organisation’s focus from ‘putting wet stuff on the red stuff’ to prevention.

I was the only woman of colour and one of two women in management. Over 99% of the 70,000 staff or volunteers were of Anglo-Saxon heritage. They wanted to address the organisation’s poor record in engaging diverse communities.

The crisis point came when I focused part of our international conference on diversity. Remember, this is a government, secular organisation. I discovered that they had an in-house pastor. He was saying grace at the conference! When I objected, the media officer said, “I don’t understand why you’re upset. Australia is a Christian country.” My senior staff said, “I don’t agree with saying the (Aboriginal) Welcome to Country, but I put up with that.” Lest there be confusion, in rhetoric at least, Australia embraces multiculturalism.

I lost the argument. I turned up at the dinner after grace, wearing a sari. They wanted me to create a cultural change but weren’t willing to change.

I won hundreds of thousands of dollars in grant money, to work with diverse community groups. My manager wouldn’t allow my staff to work on those projects, because “we can’t cater to all niche groups, like Sri Lankans.” I’m Sri Lankan.

This was my first major experience of gaslighting and racial and sexist bullying in the workplace.

As an aid worker, I’d been called “fierce.” I was tough. I worked with people of all cultures as equals. Now, I was a foreigner in my own country.

It was a defining moment in my journey to writing.

My therapist said, “People driven by altruism experience moral shock.” That continual micro assault gave me chronic PTSD. It wounded me more than any disaster or war zone. Part of me broke. When I healed, I was a different person. My brain, my person, functioned in a new and different way. A more creative way.

When my (foster) son came to me he was ten years old. Everybody and everything had been taken from him. Fostering is the hardest thing I have ever done. It has taken three years for him to feel loved and safe. My son is my karma, the best and worst of me. His humor, compassion, love and kindness inspire me. Every day I say to him, “How did I get so lucky?”

How did you develop your writing style?

Mum used to say, “There are two sides to a story and the truth.” And Mum told all sides of a story. The truth didn’t matter because her stories were beautiful. Wandering, weaving, evocative tales. Mum has bipolar disorder with psychotic breaks. I didn’t realise that until she was seventy. You grow up believing your parents’ eccentricities are normal.

When we went home to Sri Lanka, everyone told stories. The skeletons in the closet came out dancing, drinking whisky, having affairs and secret children.

Dad taught in England every four years, as part of his university sabbatical program. We grew up steeped in London’s theatre and arts culture. We traipsed through every art gallery in Europe. I saw Rudolph Nureyev dance Swan Lake with Margot Fonteyn. Google it. It was cool.

We travelled in a Kombi van, via “the hippie trail” in the 1970s. That was from London, through Europe, the Middle East to Sri Lanka. We drove in convoy with hookah-smoking hipsters. At night, there were tales around the campfire and plotting out red lines along roads without names.

Mum didn’t finish school. There were ten children in her family. They survived by stealing and rationing food. Mum’s father was an abusive drunk. My parents said, “Education is the way out of poverty.” My mother ingrained in me the importance of reading.

If you grow up watching American movies, you imbibe conventional structure. The only movie I ever watched with my parents was Elephant Man. That sparked my love of David Lynch.

My style is based on Sri Lankan oral storytelling, with a theatrical and visual quality. It’s postcards that create a feeling. I’ve been told I have a unique jumpy, visual style. Unique isn’t necessarily a good thing. A mentor said I require more from a reader, and that was a barrier.

Did you always know, deep down, that you wanted to be a writer?

I would not be a writer if every other door did not slam shut.

My life’s purpose was to be of service. I was a kick-ass aid worker. I helped thousands of people. I said, “moral imperative” and “duty to protect,” to motivate people into action. I wore my righteous indignation like a bulletproof vest.

To be a writer was so damned selfish. It was a narcissistic profession. ‘Yes, I have something worth hearing. I am Oh So Special.’

Everything I write has to attempt to create change, or I’d feel guilty.

Writing still feels self-indulgent. I love it. To mine the deepest, darkest parts of yourself, to share the giddy highs! In what other profession can it be ‘all about me’, and that’s a good thing?

When you finish my script, you will know me. Well, as well as I know myself.

You said you have a disability. Do you feel comfortable talking about that?

As a child, I had an undiagnosed medical condition. I was often too weak to stand. Some of my strongest memories are of going to school in the hospital. My medication had an unintended side effect – epilepsy.

I had my first major seizure on the first day of high school. I had been the Dux (Valedictorian) of my primary school. However, in high school, my medication and unstable epilepsy meant I was zoned out most of the time. After they changed my medication, I repeated my last year of high school.

My high school friends tell stories about me and show me photos. It’s like being photoshopped into a memory.

When I turned forty, my friend visited me in Bangkok, where I worked for Oxfam. We were crossing a six-lane intersection. I had a fit on the traffic island. The doctors tripled my medication.

Then, I realised I had never heard an entire conversation. I’d just been piecing in the gaps.

When I had a grand mal seizure, I had no control of my body. I lost consciousness. As Blanche DuBois said, “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.” That deeply shapes your psyche. You must believe that people are good and kind, because your life depends on it.

I never expected to live very long. That gives you a freedom to live fully and dangerously. I did all the things I was told I couldn’t do.

It has taken a long time to accept that my epilepsy is a disability. In my twenties, I was a manager in a disability organisation. A competitive colleague found out I had epilepsy. She then created a policy that no one with epilepsy could drive the company car. I left not long after that.

After working as an aid worker for years, I applied for a job in an Australian government disaster response team. They rejected me because I had epilepsy. I never admitted it on another job application.

In Cambodia, my nickname was nana, because I needed to be in bed by midnight. I haven’t had a grand mal seizure for a decade. It’s only now that I talk about my epilepsy. I believe that my brain’s electrical storms may be a gift, intrinsic to my creativity.

Did you get support from friends and family when you decided to put pen to paper?

My family, and their friends, think I work in a hospital. I write under a pseudonym. So, no.

When you are the child of poor immigrants, your primary focus is a career that will feed your family. There is a scarcity mentality. You can’t eat your words.

I’m Asian. My mum has dementia. Dad (when he was alive) had a neurological condition. I was expected to be their sole carer. You can’t just shake off hundreds of years of ideals of duty and honour. The matriarch (Michelle Yeoh) in ‘Crazy Rich Asians‘ captured it best. “Pursuing one’s passions. How American.”

If I was “just writing,” I had endless amounts of time. If you’re not paid to write, that’s worse.

Writing isn’t considered a ‘proper job.’ On the contrary, it’s ‘a waste of a good education.’

My friends are supportive. However, I don’t have any ‘in real life’ screenwriter friends. Curiously, five people from my high school English class became writers.

Why did you choose Phoenix Black as a pseudonym?

I named my baby Phoenix. A phoenix is a magical creature. I was single, infertile, in my forties and recovering from the Fire Service. He rose from the ashes. When a baby dies, no one says their name. They have no legacy. No one remembers them as a person except for their parent(s). Writing under Phoenix is a way for his name to carry on. I’d get a tattoo if I weren’t such a chicken shit.

Black was a combination of identifying as Black and Sirius Black. He’s my kind of guy.

What’s your writing process?

I’m a dedicated outliner. I write a rough outline of plot points.

After that, I put each scene on an index card. Father Trinity was 175 cards. I colour code characters, relationships, and plot points. I create a timeline because I write multiple nonlinear protagonists (main characters).

Then I write in a torrent. A metaphor (colour, symbol or song) and themes appear. For example, a nursery rhyme represents my character’s trauma. I ensure each scene carries the theme. I reorder or combine the cards. I rewrite.

Once it’s done, I do passes. A pass is when you go through the script and check one specific thing. For example, I read only the dialogue of one character. I do this for each character. I ensure they all sound different. Next, I do a pass on slug lines, action lines, transitions, and formatting. Finally, I do a relationship pass – Is there enough to make Ally fall in love with Flash?

I do a word search for the usual culprits – see, look, walk, now, suddenly, so, then. I delete or substitute each with a more active word. I minimise repeated words, unless it’s a deliberate device. Then it’s a slash and burn of the action lines and pronouns – she, he, them.

My playwriting mentor used to shout, “Porridge!” Naturalistic dialogue was not theatrical. Monologues, poetry, and song provided texture. He insisted we delete ‘and’ unless needed.

I scatter breadcrumbs (clues) through the script. I want someone to reach the end and realise it was all in plain sight, like in The Sixth Sense. Or try to interpret it like the meaning of a dream. I hide a lot of Easter eggs – hidden references or inside jokes. Keanu Reeves is My Muse, My Son Is A Dragon has several movie references.

I’ll read it to ensure I can hear, feel, and smell a scene. Some scenes or characters have a staccato drum beat to create tension. A monologue has a cello. Grief is crushed purple velvet. I vary the sentence length, unless the rhythm has a purpose.

Ultimately, you must give it to someone you trust to read it. I’ve had some polarising feedback from competitions or paid coverage.

Father Trinity (formerly BONEYARD) included paid feedback:

‘I thought BONEYARD was a boneyard for the rejected parts of your other scripts. I had to skip to the last five pages to work out what was happening. I wouldn’t have finished it if I wasn’t being paid to read it.’

Versus

‘This could be a cult hit! A stand out deserving a look from production companies seeking thought-provoking artistic content.’

What do you do with that?

I’ve paid for lots of coverage and lots of competitions. I won’t do that again.

I often write in a café. If I’m crying while writing, it’s probably a good scene.

I use a paper notebook. When I drive, I use voice to text, or my son takes notes on my phone. The bulk of my writing is on a laptop. It’s easier to keep up with the speed of thought. When I type, I go into a meditative state. Maybe it’s the patter across the keyboard, like rain.

What genre do you write in?

Many writers specialise in one genre. For example, horror, drama, or comedy. This makes them and their stories easier to market. That’s not going to be my journey.

It doesn’t matter whether it’s a writing assignment or a spec. I feel that stories come to me. I’m just the person who has the honour of writing them down.

A couple of notable exceptions: Romance and comedy.

If I write romance, everyone dies, or it ends badly. That probably reflects my love life. Romance requires an optimism about love that’s not in me. For now, at least.

Comedy is the province of brilliant, quick-witted people. I’m in awe of them. I can recount funny things that happened. Like waking up to my foster son, massaging his shoulders with my vibrator. Comedy isn’t my strength. I can laugh at myself heartily. People laugh with me at me.

If forced into a pigeonhole, I write nonlinear social dramas with multiple protagonists.

Self-belief

A writer needs to have a solid, albeit sometimes wavering, belief in their story and themselves.

Will Keanu Reeves Is My Muse, My Son Is A Dragon be read by Keanu? Will Father Trinity turn up on the desk of David Lynch? It’s in my nature to believe in the impossible.

Father Trinity is my favourite child. He’s quirky. I will always believe in him. I will cheer for him until the end.

Income

Income is the greatest and most unaddressed barrier. Mentorships, coverage, competitions, pitch fests, conferences, workshops, retreats. It costs thousands of dollars. Forget college or moving to LA. An entry-level writer’s room position isn’t enough to feed a family.

Time

Some writers get up at 5am, create word magic then rush to a day job. I need to eavesdrop on people with complicated coffee orders. I need to take a long shower. There is nothing like the flow of water on skin to solve plot problems. Ideally, I need a block of time with good coffee and café chatter for my brain to click into gear. Yet, perversely, deadlines make me really productive.

Competing priorities

Having a child has made me more focused. Time is more precious. I often feel like a terrible mother. Time spent writing or researching could be invested in my child or my mother, while she recognises me. Money spent on mentorships etc., could be spent on holidays. Writing is time away from your family. It’s a very personal sacrifice.

Does coming from a diverse background pose particular challenges for you?

The concept of diversity grates on me. By diversity, we mean anyone who isn’t a white straight Christian man without a disability. That’s most of the world. How is the talented majority now considered a niche group? If diversity implies minorities, how does it become the culturally rich majority? How does the ocean squeeze through a tiny hole?

I’m going to interpret diverse, in this instance, as traditionally underrepresented groups.

A three-act, single-protagonist, linear structure is the revered standard for ‘how to tell a story.’ It is familiar. Familiarity makes it easier to follow. There are conventions around many other story elements. This includes pacing (the speed at which the story moves) and each scene having conflict (a clash of wants, needs or characters). Anything outside of that is indie or experimental. Worse, it may be interpreted as the writer not understanding story. My work doesn’t strictly follow these conventions.

‘Unique’ is a tough sell, and movies are a business. If your work can’t be directly compared to what’s known, selling you takes extra work for managers. The business thereby systematically excludes voices and styles that are outside the norm.

I can pitch. I can market myself. I can tell a story according to the prevalent screenwriting formulas: The Three Act Structure, Hero’s Journey, or Save The Cat, etc. It just won’t represent my culture, upbringing or oral storytelling tradition. Still, I can do it.

My work has an Asian mum reciting poetry, a man’s dying monologue, and lyrical speech. It’s tapestried with metaphor.

This is entirely unsurprising if you were brought up on theatre, poetry, and art. One reader said, “Including poems is pretentious.” Another said, “That’s not what (the character) would say.” That’s a direct quote from my Asian son, on whom that character is based.

Reader feedback on Father Trinity:

‘An ingeniously plotted film in the psychological vein of David Lynch, with the operatic grandeur of Leos Carax. The world-building, symbols and metaphors show real vision with an experimental structure. This is awards bait that doesn’t underestimate the intelligence of the audience. This has the potential to be dissected by critics and audience repeatedly.’

That is not the compliment you think it to be. A mentor said, “We’ve already got David Lynch.” ‘Awards bait’ and ‘intelligent audience’ means not commercial. ‘Dissected repeatedly’ means people might not understand everything immediately. In the commercial downturn of film, production companies understandably favour safe.

I met Fiona Shaw (Killing Eve, Harry Potter) at a Sri Lankan literary festival. We discussed the use of language by Shakespeare and Beckett. Actors want lyrical language, poems and monologues.

There’s what I can only explain as a therapy culture in America. Everyone needs to understand a character’s motivation. Every detail has to be explained. There can be no secrets left untold. Every character has to be deep and have agency (control their situation). That bears no resemblance to reality. If we knew everything about ourselves, therapists would be out of a job.

The critiques I’ve received reflect a lack of understanding of a culture that is not Western. For example, I’ve had comments that my stories are ‘not American’ and ‘might sell better in Europe.’

The vast differences between American versus European and Asian movies, show that there is another way. If ‘what movies should be’ is based on what was and what is, how do we evolve? Do we want to evolve?

One issue is peculiar to Australian culture.

Many Australians judge exotic travel, theatre, or galleries as elitist. Forget about poetry, opera or ballet. I dumb down my vocabulary. Australians have ‘Tall Poppy Syndrome.’ Anyone who stands out from the crowd is cut down to size. You don’t talk about wins, except for sport.

Australians are often successful overseas, before their talent is embraced at home. It takes effort to overcome the instinct to never self-promote.

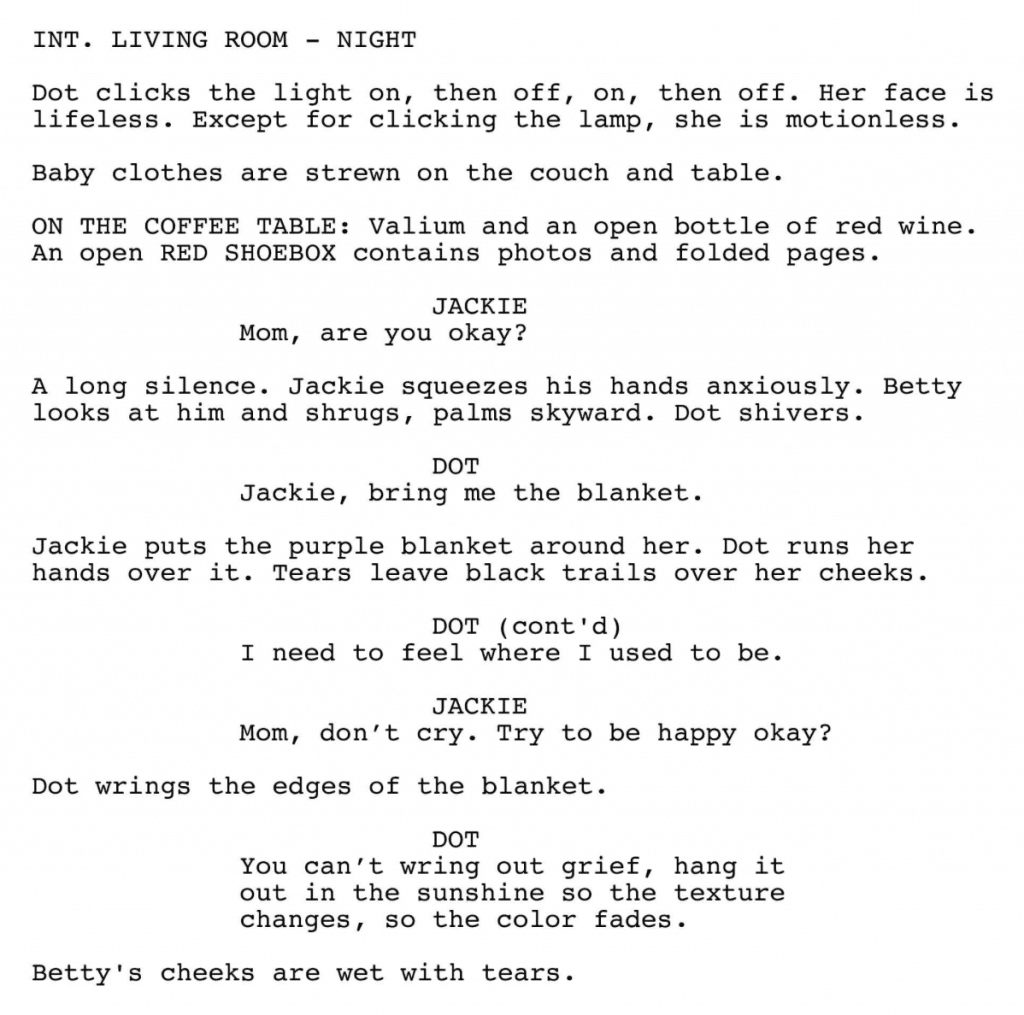

Excerpt from Father Trinity

What is the greatest challenge to ‘making it’ in the industry?

Connections! And an inherent bias in the system.

Connections

They say success is talent means opportunity. Opportunity means connections.

A writer needs a champion to influence a tastemaker. Or a bucket load of fairy dust.

A tastemaker is someone in the biz who can create a taste for something, even a project seen as unpalatable. Sure, you could win a competition leading to well-regarded managers vying for you. Someone could find you on social media or a writer’s list. That is very, very rare.

To get your work read, it must get into the right hands. You need a credible connection to gush on your behalf. You have a decent chance if your work gets directly to the right person.

Most often, your script goes through several layers of readers. Generally, readers learn storytelling in college. So your work is judged against a rigid framework of ‘what makes a good story.’ On top of that, they apply lenses: How easy is this to sell? How likely are we to attach the talent? How much will it cost to make it?

Everything Everywhere All At Once would not have been made, if it was written by an unknown writer and had to go through multiple layers of unknown readers.

Without connections, you have to be a marketing machine. From social media to pitching, developing pitch decks, and networking. You have to master it all. Then you have to be lucky.

I’ve made strong friendships and connections through Twitter. I gained 5000 followers in less than a year. I have a website, pitch decks, profiles, and contest placements. I pitched Keanu Reeves Is My Muse, My Son Is A Dragon on a podcast, with actors acting out pages. As a tonal taster for Father Trinity, I wrote a monologue performed by Alex Osmond and Adam Files. Each performed it from the viewpoint of a different protagonist – movie star Flash or grieving stagehand Ace. I’m on Coverfly’s Top 20 family projects of all time. I’m on the Grey List’s best scripts from writers over forty. Writers have kindly read my work and tried to connect me to those in the biz.

My friend’s dad met “a lovely young man in show business. Shall I introduce you?” That lovely young man was Craig Pearce, the incredible screenwriter of Elvis and Romeo+Juliet. Craig told me his break came through his best mate – Baz Luhrmann. Baz was adapting his play into a feature, ‘Strictly Ballroom.’ Script development was not going well. Baz convinced the company to let his best mate, an actor, write the screenplay. Talent meets timing meets connections.

I told Craig everything that I was doing to promote my work. His advice? “Make something. Write something someone will make. I realise that’s the chicken and the egg.”

Biases

Without addressing bias, different voices cannot break through. Unless they have a connection.

I don’t speak with the authority of someone inside the Hollywood sanctum. However, I can speak with authority on the barriers to behavioural change. Change requires us to address bias, create structures and have those in power be genuine change makers.

There’s a view that if you’re not on the inside, your opinion is ill informed or sour grapes. ‘You can’t criticise us if you’re not one of us.’ The corollary is, to become one of us, you need to conform to our views.

There is a flaw in the prevailing argument that to make something different, you have to first make something that is not. Don’t be different if you want to be or are different.

With sufficient insight and commitment, the lack of diversity isn’t a difficult problem to solve. I’m available for a highly paid consultancy. It’s certainly more complex than the token number of feeder programs and competitions. Enter this diversity competition for $65 because we really want diverse voices! Enter this paid feeder program, if you can afford it.

It’s a specious argument that writer’s rooms don’t reflect the population, because of a lack of available talented (for example) Black or disabled writers. It infuriates me to hear actors complain about the dearth of authentic parts for female actors over forty. Those brilliant writers and scripts exist.

Without getting technical, I’ll cover a few of the many cognitive bias basics.

By nature, we favour the status quo. We are defensive when we are held to account.

We favour people that relate to us. We ‘click.’ We have a shorthand because we have a shared experience. To get into the ‘in-group’, you have to change. You have to tell a story they can identify with or at least tell it in a way they can understand.

A belief becomes more entrenched when it is challenged – the Backfire Effect. You can only challenge the group when you are in the group. You cannot get into the group if you challenge the group. To speak up as a lone voice in a less powerful position, challenges the authority of the group.

To compound these difficulties, we pay attention to information that confirms our beliefs. We ignore facts that don’t support our pre-existing ideas. For example, we study the ‘Save the Cat’ writing formula, because we believe that is how a story should be written. We ignore different methodologies because they don’t support our ideas of what makes a story.

There is pressure on Hollywood to make movies with a diverse cast, diverse writers and diverse stories. It’s embarrassing for the demographics of success to be revealed.

Who is missing? If you want to hear those voices, the system has to change, not the writers.

If no one is disagreeing with you, you have a problem. People are afraid to speak up or everyone around you is the same. The best outcomes come from diversity of thought.

I’ll very briefly touch on a few biases: Race, gender, age and caregivers.

Whilst I was studying filmmaking, the only white male in our group said, “You have to be a Black lesbian over forty in a wheelchair” to get an opportunity. None of the others voiced opposition. Why? He spoke loudest, most often, and had strong opinions. He wore a suit. All of the teachers were white men. He was about to make a movie, via his connections, who were all were white men. He therefore became the dominant minority. The irony was lost on him.

News flash: If you tick a diversity box, the red carpet doesn’t magically unroll.

I am emphatically not saying that white writers should be excluded from new positions. Everyone should have a chance. I know white male writers, who’ve been told by management companies, “I won’t even put you forward. They’re only looking for diversity hires.” Creating that schism is entirely counterproductive.

Referring to all white straight men as a homogeneous group, is as unhelpful as talking about all Black people as if they’re the same. You don’t make allies by alienating people.

However, every room should be representative of the makeup of the population. The exceptions are shows about a particular cultural group. For example, you can’t have one Black writer on a show about a Black family. And please, Asian writers don’t just write Asian parts!

Certainly, our successful writers, directors and actors in Australia have a definite skew.

Without thinking, write a list of the top ten Australian actors. Notice anything?

In 2021, the majority audience, for most of the box office performers, were people of colour. Yet only three of the ten leads in those top performers were not white. Moreover, films written or directed by people of colour in 2021 had significantly more diverse casts than those written or directed by white men. Films that had at least a 21% diverse cast, enjoyed the highest median global box office receipts.

Greater diversity of screenwriters translates to better box office receipts.

The success of Everything Everywhere All At Once, with its predominantly Asian cast and wacky storytelling, is remarkable. Different works. Diversity isn’t a niche. It’s your audience.

Gender: Smart women telling uncomfortable truths are aggressive, defensive, and difficult troublemakers. Men saying the same thing are assertive, true to their values, uncovering the issues, and speaking their truth.

We want to hear all voices, but please keep your rage soft.

Uncomfortable truths make us uncomfortable. Instinct tells us to deal with people who won’t challenge us. We build rapport quickly with and favour people who ‘get’ us. It’s difficult to relate to someone whose worldview is foreign.

Ageism: Few entry-level positions for people over forty means few fresh outlooks from people over forty. Movie stars over forty want roles with an authentic voice, a voice that understands what it’s like to be over forty.

Caregivers: Primary caregivers of children or ill parents are most often women. How many single mums are in writers’ rooms or on set? Unpredictable, long hours and the cost of childcare exclude them. However, some female showrunners and directors accommodate caregivers, because they are caregivers. It can be done.

There is an intersectionality of bias. For example, a Black lesbian over forty in a wheelchair experiences a conjunction of unconscious biases, not a conjunction of opportunity.

If you want to fly, you’ve got to ruffle some feathers. Different isn’t wrong. It’s just unfamiliar to the people guarding the gates.

– Phoenix Black

I’m an Asian woman of colour, over forty, with a disability in management. I challenge the status quo just by walking into a room.

Being a change agent is a rocky, lonely path. My best friend said, “Why can’t you just leave it alone? Why do you have to get into the fight?” I answered, “The problem is that not enough people get into the fight. The problem is apathy and a lack of empathy.”

People who have not been ‘other’ don’t understand that, in some way, every day is a fight.

People in traditionally underrepresented groups will never find their place if they fight alone. People outside of those groups also have to call for accountability and action. To be silent is to be complicit.

Unconscious bias is a key area of interest for you. Can you expand on that a little more?

Unconscious bias is when you unconsciously think or feel something about a group.

Imagine your only daughter says she’s getting married. She’s twenty. You don’t know the person, and she’s not giving you details. You can see she’s nervous. She’s invited them to dinner. You’re freaking out. You think ‘I can accept this person as long as they’re not –’

The end of that sentence is your unconscious bias.

Movies teach us unconscious bias: who is sexy, cool, should lead, who are heroes. In the most popular tween movies, that’s white men.

Captain America, Superman, Batman, Spiderman, Antman, Thor, Wolverine, most of the Harry Potter World, and Twilight. Even Jack Sully in Avatar, before he turned blue.

I want my 13-year-old Korean son to embrace his Asian culture. To believe he can be the hero in his story. Where are the English-speaking kid’s movies that put Asians in the lead?

We are choosing to produce movies that will not just influence but define.

Story conventions are biased against diverse stories.

If you want to fly, you’ve got to ruffle some feathers. Different isn’t wrong. It’s just unfamiliar to the people guarding the gates.

In order for diverse stories and diverse writers to have any chance in this industry, the lens by which we view story needs to be adjusted. Diverse stories do not conform to Western conventions. Diverse stories have different structures, character arcs, character agency and pacing. It’s all different.

To quote author J. Koen Alonso, “BIPOC stories aren’t just Western structures with different skin colours and mythologies.”

The current expectation is that every character has to transform starkly, preferably for the better. Each scene should have conflict. In many Asian cultures, conflict is distasteful. It shows weakness and a lack of respect for tradition. Our personal stories are often of the good guy coming last.

Of course, no one Asian person represents the entirety of Asian culture and storytelling. RRR and Pathaan have character agency in overdrive.

My dear American friend visited the US after five years of living in Cambodia.

“I finally understand the difference between Americans and Asians. When Americans see a mountain in their way, they punch through it. Asians go around, like a river. They wear the mountain away.”

What advice would you give newbies who want to pursue scriptwriting? Why?

Let’s assume you’ve developed your craft. You can take feedback without being crushed. You know how to research and when to stop. You know how to edit. You overcome the writer’s self-loathing, self-criticism and self-doubt. Many writers have mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. You work at least two jobs – one in the imagination and one in the real world. Maybe you care for children or ill parents. You manage all of that and have a market-ready product. You know how to finish one project and move onto the next. You have grit. You know it might be your third or twelfth script that gets sold. You know how to market yourself. That’s the bare minimum you need to be a writer.

More specifically –

Get a life. If you want to write something interesting, be interesting. If you have no life experience, get some. Travel, meet people outside of your usual crowd, and volunteer. If you have something unique about you, such as a disability or tragedy, bring that into your scripts. I’m not saying you have to do cocaine to write Cocaine Bear.

Continue to work on your craft. Get feedback. Learn what feedback to take and what to reject.

Toughen the hell up. Persist.

Make genuine connections with other writers and people in the movie business. Give to the writing community more than you take.

Volunteer for student or short films. Understanding the process, from page to screen, improves your writing. My current project came through an actor on a student film. He knew a producer looking for a screenwriter.

Make something. I hate giving this advice because I hate that it’s true. People are more likely to read your script if they see your work. So find a film crew looking for a script. Or learn to film your own work.

Other writers are not your competition. We are all in the same ship. We rise together.

Surround yourself with cheerleaders. Plenty of family and friends will ask, “Where is this going?” “What’s your plan B?” You’ll have enough self-doubt without others heaping on.

Look after your mental health and your back. It’s a solitary job. You dwell on your own thoughts and sit on your ass a lot. Connect with people. Stretch.

Overnight success is a one-in-billion chance. Learn how to market yourself. Unfortunately, there’s no script fairy coming to help you! You can create a masterpiece, but the right person has to read it.

Most importantly, you don’t need everyone to love your work. You just need to have the one right person. It’s like love. And I’m still searching for The One.

Tingling! Keanu Reeves Is My Muse, My Son Is A Dragon is a Top 5 finalist in the Big Break Screenwriting Comp!!! Thanks @finaldraftinc for supporting my out-there fantasy family drama.

— Phoenix Black:Keanu Is My Muse, My Son Is A Dragon (@PhoenixBlackNow) December 2, 2022

Congrats to all the other finalists. #KeanuReeves https://t.co/rTgKoty3iM